The year they canceled Halloween

LiveNOW & Then full episode: Archived coverage of the 1982 Tylenol murders

The children who experienced the scarier-than-usual Halloween of 1982 are grown up now, with children of their own. But some will never forget the Tylenol cyanide murders that year. Here's how it was covered on TV news at the time.

It’s Halloween again, which means kids everywhere are dressing up for trick or treat. But before the little beggars can tear into their treats, many of their parents will have issued that same warning we heard as kids: "Be sure to inspect that candy for razor blades or poison!"

Where did that idea come from? Experts say it’s a fear that stretches back decades, with very little actual basis in reality. But there are two incidents that may have helped inspire it.

First, there was a boy who died from a poisoned Pixie Stix he got on Halloween in 1974. It turned out, though, his father did it. Ronald Clark O’Brien was convicted of the murder and executed a decade later.

Ronald Clark O’Brien, who murdered his son with poisoned candy on Halloween, seen in prison before his execution.

But no one was every truly convicted of the Tylenol cyanide murders of 1982 – a shocking crime that left seven people dead, inspired deadly copycats, and prompted communities across the country to cancel trick or treat that year.

What were the Tylenol cyanide murders?

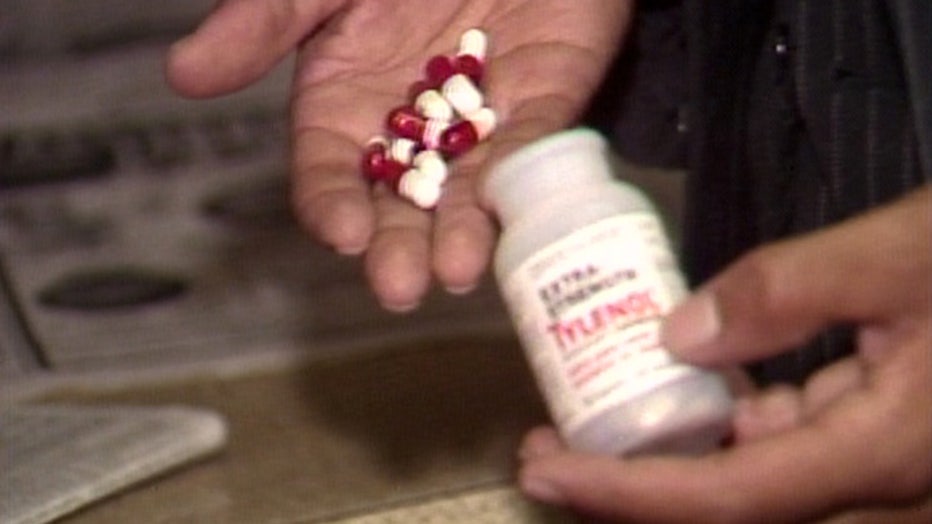

Bottles of extra-strength Tylenol were poisoned with cyanide.

When you opened a bottle of Tylenol in the early 1980s – or any such product – you didn’t see a protective seal. Now, it's the law because of what happened in the Chicago area starting on Sept. 29, 1982.

Early that morning, 12-year-old Mary Kellerman came down with a sore throat and a runny nose, so her parents gave her one extra-strength Tylenol. Hours later, she was dead.

Over the next several days, six more people in the Chicago area died suddenly after taking what was, at the time, the best-selling over-the-counter pain reliever.

Three Tylenol poisoning victims, all from the same family, were buried on Oct. 5, 1982 in suburban Niles, Illinois. The victims were Stanley Janus and Adam Janus, and Stanley Janus' wife, Theresa Janus. (Bettmann via Getty Images)

Investigators soon realized that each victim had swallowed a tablet laced with a lethal dose of cyanide. The pill manufacturer, Johnson & Johnson, determined that the bottles had been tampered with after leaving the factory.

Someone had taken the bottles off the shelves at several drug stores, added poison to the capsules and then put them back, with unwitting customers purchasing the deadly concoctions.

Fear spreads across the country

A clerk removes Tylenol capsules from the shelves of a pharmacy September 30, 1982 in New York City after reports of tampering. (Photo by Yvonne Hemsey/Getty Images)

Stores immediately pulled the drug from their shelves, but consumers across the country were still uneasy as they hunted through their medicine cabinets for bottles with the questionable manufacturing code.

"They took my name and address and told me they would send someone out this morning to pick up the pills," explained one Austin, Texas resident who called Poison Control after realizing he’d bought one of the possibly contaminated bottles.

Poison control centers were flooded with calls from Americans concerned about Tylenol.

"We are advising people that, until we have an understanding of the magnitude of the problem, that they avoid taking this particular product until we feel certain it would be safe for them to take it," explained Dr. Richard Weisman of New York’s Poison Control Center.

The effect on Halloween

Millions of kids were ready to hit the streets for trick or treat that year – popular costumes included Pac-Man, Star Wars, and the star of 1982’s biggest movie, E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial – but with the poisonings still unsolved, many communities issued warnings or even canceled festivities altogether, fearing kids could be the next target.

"We decided that they are not going trick or treating and I am going to buy them a toy instead," Long Island mother Susan Rund told WNYW. "I just returned candy…not because there’s any problem but just because I’m afraid to give it to them."

"I can tell you how I feel as a parent that I wouldn’t want my kids out there this year because no matter how close you look at the package, there’s still some possibility that someone might have done something," offered San Jose, California’s police chief, Joseph McNamara.

In all, more than 40 cities across the country canceled trick or treat events that year.

Case remains unsolved

Days after the poisonings, Johnson & Johnson received a letter taking credit for the murders and threatening more – unless $1-million was wired to a Chicago bank account.

Investigators quickly identified the author as a man named James Lewis. After a two-month manhunt, he was arrested in New York when a sharp-eyed librarian recognized him. The next year, Lewis was convicted of attempted extortion and sentenced to prison – but he continued to insist he wasn’t the actual killer, and he was never charged with those crimes.

James Lewis is arrested on charges of attempted extortion.

Roger Arnold, a Chicago dockworker, also got investigators’ attention when a bartender told police that Arnold had been talking about cyanide. Arnold later shot and killed another man, mistaking him for the bartender. He was sentenced to prison for the murder.

Meanwhile, Lewis was released from prison in 1995. Investigators kept an eye on him and even searched his home in 2009, but never ended up filing charges. He died of natural causes in 2023 at the age of 76.

Legacy of the case

Today, pill bottles and other items come packaged with so many anti-tampering features, it’s become a punchline. Generations of Americans have grown up without giving the foil seals and push-to-twist caps a second thought.

Meanwhile, the children who experienced the scarier-than-usual Halloween of 1982 are grown up now, with children of their own. But some will never forget what happened in the Chicago area starting on Sept. 29, 1982.

"That was the year they canceled Halloween," retired FBI agent Roy Lane recalled years later.

More from the archives

- 50 years of hip-hop: Expert predicts future of music genre – and females are at the forefront

- 2003 Northeast Blackout: A look back at the historic power outage

- Jimmy Hoffa case: A look back at his infamous disappearance

- Decades later: The infamous O.J. Simpson police chase

FOX 32 Chicago and Rebecca Rosenberg with FOX News contributed to this report.