Slavery reparations: How the US can follow one town's effort to right dark past

'The Big Payback': Erika Alexander, Whitney Dow discuss slavery reparations

The documentary, co-directed by Alexander and Dow, highlights an alderwoman's fight for reparations for slavery descendants in an Illinois town. The PBS documentary will premiere on January 16, 2023, at 10:00 p.m. ET.

Martin Luther King Jr. Day kicks off another year of advocacy on a racial justice agenda — from police reforms and strengthening voting rights to solutions for economic and educational disparities.

One proposed solution is reparations — compensating Black Americans today for the suppression that has spanned generations due to institutional wrongs or discriminations, such as slavery. It’s been more than 400 years since the first enslaved Africans arrived in America, and the effects of America’s darkest chapter are still being discussed today.

Advocates for reparations believe the harm suffered by descendants of enslaved people is still prevalent in today’s culture through discriminatory laws and actions in all facets of life, from housing and education to employment and the legal system.

RELATED: Airbnb bans listings where enslaved people used to live or work

A 2019 study showed few Americans are in favor of giving reparations to descendants of enslaved Black people in the U.S. Most Black Americans, 74%, favor reparations, compared with 15% of white Americans. Among Hispanics, 44% were in favor.

Further dividing the conversation is what reparations, if any, should look like. Only 29% of Americans say the government should pay cash reparations, according to the Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll.

The history of reparations in the U.S.

For centuries, state and federal governments had tried to make amends for communities that were once disenfranchised.

RELATED: Alabama town abolishes police department after officer's slavery text surfaces

The idea of reparations is nothing new, even in America. For centuries, countries around the world have paid reparations for various wrongs, such as in Germany to Holocaust survivors.

And while some U.S. cities and even states are taking a closer look at reparations, the push for federal reparations is gaining momentum.

"It’s urgent. It’s urgent care that we need on this measure, more importantly, we need everybody, everybody to understand, how it will help everybody," filmmaker and actress Erika Alexander told FOX Television Stations.

Alexander co-directed a new documentary on reparations in America, "The Big Payback," which is set to air on PBS on MLK Day.

Erika Alexander and Whitney Dow attend "The Big Payback" Premiere during the 2022 Tribeca Festival at Village East Cinema on June 11, 2022 in New York City. (Photo by John Lamparski/Getty Images for Tribeca Festival)

Here is a look at what those reparations could entail, and where they’ve already been started in the country:

Reparations: The definition and the misconceptions

Reparations are "measures to redress violations of human rights by providing a range of material and symbolic benefits to victims or their families as well as affected communities," according to the definition used by the United Nations.

Regardless of what — or who — the reparations are for, they are more than just a paycheck, which is a common misconception.

"People think it’s only about money. They think it’s about revenge. They think it’s about, ‘You owe us...pay us back just because of our pain and suffering,’" Alexander continued.

"But the truth is," she continued, "these measures or these things they put inside the system still exist...I think the misconception is that it doesn’t exist, that it’s over, that we just need to move on. But do you understand the boulder that’s still on our shoulders?"

RELATED: The Embrace statue unveiled in Boston on MLK weekend

Besides money, reparations could be made through actions such as affirmative action, scholarships, or land-based compensation, according to the University of Massachusetts Amherst. "Reparation must be adequate, effective, prompt, and should be proportional to the gravity of the violations and the harm suffered," the United Nations’ definition continues.

Another misconception is that the offending party gets to decide how to make amends, but reparations should actually be decided by those who have been wronged.

"If you’ve committed a crime against somebody, if you’ve committed an offense against somebody, you don’t get to decide what the ‘repair’ is. You just have to decide that it’s made," said fellow co-director of "The Big Payback" and award-winning documentarian, Whitney Dow.

A third misconception, and one that the documentary explores, is that reparations aren’t important or necessary for white Americans. But, as Alexander, Dow and other advocates explain, reparations are necessary to heal and unite — "transform" — the country and move forward.

"When we wrong somebody, or we're on the wrong side of a moral question," Dow continued, "it eats away at us. And the weight that’s lifted when you actually apologize...even if it’s not accepted, but making an attempt at repair really is transformative."

Reparations on a local level

In 2021, the city of Evanston, Illinois, became the first city in the country to pass legislation to pay Black Americans tax-funded reparations for past discrimination and the lingering effects of slavery.

The measure was spearheaded by Alderman Robin Rue Simmons, whose story is the main driving force of Alexander and Dow’s documentary.

"Seeing this story with Robin Rue Simmons, actually forming [the legislation], it was so inspiring to see," Dow said. "She kind of did what nobody else would do. She showed that it was possible."

A man walks by a sign welcoming people to the city of in Evanston, Illinois, on March 16, 2021. (Photo by KAMIL KRZACZYNSKI/AFP via Getty Images)

Now, with a model of sorts to look at, several communities and states are pushing forward with their own reparations.

In California, a task force is deliberating how financial compensation might be calculated and what might be required to prove eligibility. The state-level task force is the first of its kind in action in the country, made up of economists who have already released a groundbreaking interim report.

Just last month, a similar task force was approved in Boston and the St. Louis mayor also appointed a reparations committee.

(L-R) Whitney Dow, Robin Rue Simmons, and Erika Alexander attend a Screening of "The Big Payback" at the Apollo Theater on June 19, 2022 in New York City. (Photo by Monica Schipper/Getty Images for Color Farm Media)

In Providence, Rhode Island, a $10-million budget has been approved for reparations. And public officials in New York are trying anew to create a reparations commission in the state.

Meanwhile, Simmons has gone on to found the nonprofit FirstRepair, which works nationally to educate and equip those working to advance local reparations policies — a priority that Simmons, the documentary filmmakers, and other advocates say is the first step to seeing reparations on a national level.

"Washington will follow if local communities lead," Dow said. "It really needs to become something all local communities recognize, that they’re a part of this paradigm and a part of this healing."

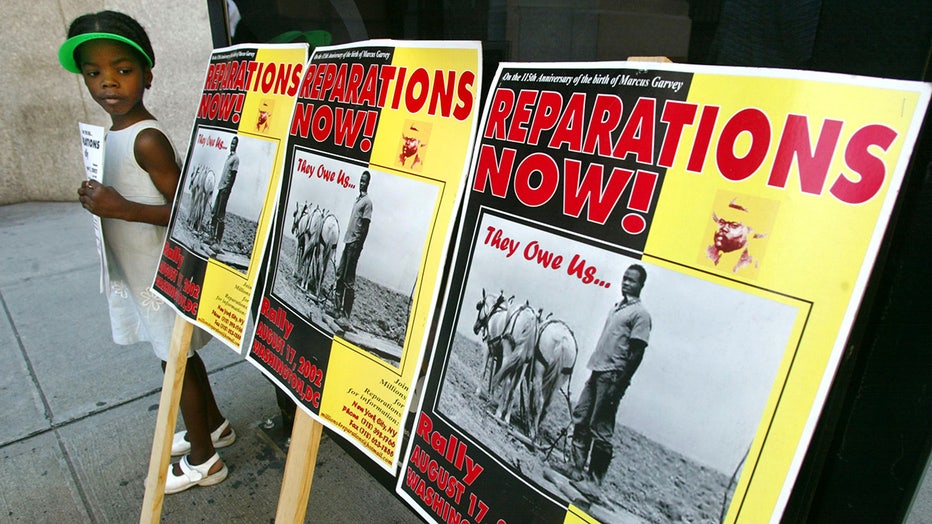

File: Lindi Bobb, 6, attends a slavery reparations protest on August 9, 2002 in New York City. (Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images).

Reparations on a national level

The push for reparations for descendants of enslaved people has existed in Congress for decades.

The bill, commonly referred to as H.R. 40, was first introduced by Rep. John Conyers, D-Mich., in 1989. The "40" refers to the failed government effort to provide 40 acres of land to newly freed slaves as the Civil War drew to a close.

H.R. 40 would create a study commission that would recommend ways to educate Americans about slavery and discrimination and appropriate remedies, including how the government would offer a formal apology and what form of compensation should be awarded.

Conyers reintroduced the bill every session until his resignation in 2017. He died two years later.

But in April 2021, a House panel advanced the long-stalled bill, thanks to its reintroduction from Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, D-Texas, who rallied 173 co-sponsors. She said the descendants of slavery continue to suffer from the legacy of a brutal system and the enduring racial inequality it spawned.

Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee (D-TX) speaks during a hearing on slavery reparations held by the House Judiciary Subcommittee on the Constitution, Civil Rights and Civil Liberties on June 19, 2019 in Washington, DC. (Photo by Zach Gibson/Getty Images)

"The government sanctioned slavery," Jackson Lee said. "And that is what we need, a reckoning, a healing reparative justice."

Though, prospects for the final passage of H.R. 40 remain poor in such a closely divided Congress.

Both white and Black Americans have an important and necessary part in making reparations happen, though the roles are vastly different.

"[White Americans] actually have the simpler job in this, is that our job is just to advocate for reparations. It’s not to determine what that reparation is," Dow explained. "White people, all we have to do is get on board the train of making this happen.

"[Black Americans] have a much, much bigger problem with the internal base of what actually reparations should be, who should get it, how much, how it’s distributed and in what way — that’s a much, much bigger task."

"Reparations is more for [white Americans] than it really is for Black Americans. And the reason I say this is, of course, it will help us, but...white superiority overall is an illness. It must be stopped," Alexander agreed.

"[Reparations] will actually go at the core and the toxicity of what ails us as Americans."

For more information:

- To read more about H.R. 40, click here.

- For more information on "The Big Payback," click here. The film makes its television debut on PBS at 10 p.m. ET on Jan. 16, 2023 (check local listings). It will also be available to stream on the PBS Video app.

This story was reported from Detroit and Los Angeles. The Associated Press contributed.