Jerry Moss, co-founder of A&M Records and Rock Hall of Fame inductee, dead at 88

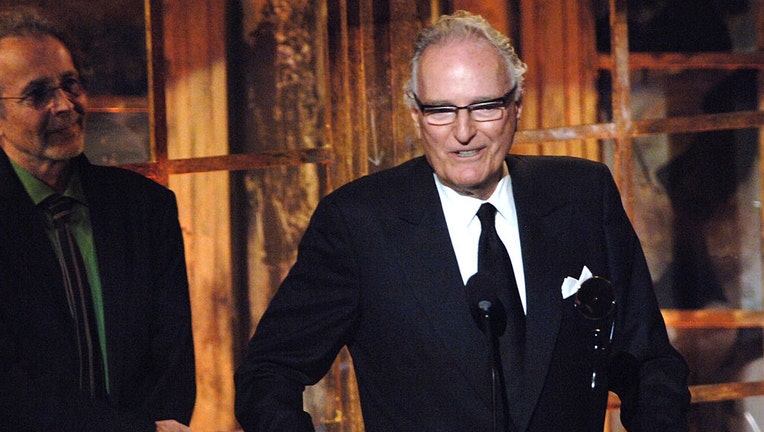

Herb Alpert and Jerry Moss, right, inductees during 21st Annual Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction Ceremony - Show at The Waldorf-Astoria in New York City, New York, United States. (Jeff Kravitz/Getty Images/FilmMagic, Inc)

Jerry Moss, a music industry giant who co-founded A&M Records with Herb Alpert and rose from a Los Angeles garage to the heights of success with hits by Alpert, the Police, the Carpenters and hundreds of other performers, has died at 88.

Moss, inducted with Alpert into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in 2006, died Wednesday at his home in Bel Air, California, according to a statement released by his family. He died of natural causes, his widow Tina told The Associated Press.

"They truly don’t make them like him anymore and we will miss conversations with him about everything under the sun," the statement reads in part, "the twinkle in his eyes as he approached every moment ready for the next adventure."

For more than 25 years, Alpert and Moss presided over one of the industry's most successful independent labels, releasing such blockbuster albums as Alpert's "Whipped Cream & Other Delights," Carole King's "Tapestry" and Peter Frampton's "Frampton Comes Alive!" They were home to the Carpenters and Cat Stevens,Janet Jackson and Soundgarden,Joe Cocker and Suzanne Vega, the Go-Gos and Sheryl Crow.

RELATED: Clarence Avant ‘Godfather of Black Music’ dies at 92

Among the label's singles: Alpert's "A Taste of Honey," the Captain and Tennille's "Love Will Keep Us Together," Frampton's "Show Me the Way" and "Every Breath You Take," by the Police.

"Every once in a while a record would come through us and Herbie would look at me and say, ‘What did we do to deserve this, that this amazing thing is going to come out on our label?’" Moss told Artist House Music, an archive and resource center, in 2007.

His music connections also led to a lucrative horse racing business that he owned with his second wife, Ann Holbrook. In 1962, record manufacturer Nate Duroff lent Alpert and Moss $35,000 so they could print 350,000 copies of Alpert's instrumental "The Lonely Bull," the label's first major hit. A decade later, Duroff convinced Moss to invest in horses.

The Mosses' Giacomo, named for the son of A&M artist Sting, won the Kentucky Derby in 2005. Zenyatta, in honor of the Police album "Zenyatta Mondatta," was runner-up for Horse of the Year in 2008 and 2009 and won the following year. A hit single by Sting gave Moss the name for another profitable horse, Set Them Free.

Moss made one of his last public appearances in January when he was honored with a tribute concert at the Mark Taper Forum in downtown Los Angeles. Among the performers were Frampton, Amy Grant and Dionne Warwick, who wasn't an A&M artist but had been close to Moss from the time he helped promote her music in the early 1960s. While Moss didn’t speak at the ceremony, many others praised him.

"Herb was the artist and Jerry had the vision. It just changed the face of the record industry," singer Rita Coolidge said on the event’s red carpet. "Certainly A&M made such a difference and it’s where everybody wanted to be."

Moss' survivors include his second wife, Tina Morse, and three children.

Born in New York City and an English major at Brooklyn College, Moss had wanted to work in show business since waiting tables in his 20s and noticing that the entertainment industry patrons seemed to be having so much fun. After a six-month Army stint, he found work as a promoter for Coed Records and eventually moved to Los Angeles, where he met and befriended Alpert, a trumpeter, songwriter and entrepreneur.

With an investment of $100 each, they formed Carnival Records and had a local hit with "Tell It to the Birds," an Alpert ballad released under the name of his son, Dore Alpert. After learning that another company was called Carnival, Alpert and Moss used the initials of their last names and renamed their business A&M, working out an office in Alpert's garage and designing the distinctive logo with the trumpet across the bottom.

"We had a desk, piano, piano stool, a couch, coffee table and two phone lines. And that for the two of us worked out very well, because we could go over the songs on the piano and make phone calls to the distributors," Moss later told Billboard. "We also had an answering service at the time. I'd do all my own billing."

For several years they specialized in "easy listening" acts such as Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, Brazilian artist Sergio Mendes and the folk-rock trio the Sandpipers. After attending the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967, rock's first major festival, Moss began adding rock performers, including Cocker, Procol Harum and Free.

One of their biggest triumphs was "Frampton Comes Alive!" a live double album from 1976 that sold more than 6 million copies in its first year and transformed Frampton from mid-level performer to superstar.

"Peter was a huge live star in markets like Detroit and San Francisco, so we made a suggestion that he make a live record," Moss told Rolling Stone in 2002. "What he was doing onstage wasn't like the records — it was outrageously better. I remember being at the mix of 'Frampton Comes Alive!' at Electric Lady studios, and I was so blown away I asked to make it a double album."

A&M continued to expand their catalog through the 1970s and '80s, taking on the Police, Squeeze, Joe Jackson and other British New Wave artists, R&B musicians Janet Jackson and Barry White and country rockers 38 Special and the Ozark Mountain Daredevils.

By the late '80s, Alpert and Moss were operating out of a Hollywood lot where Charlie Chaplin once made movies, but they struggled to keep up with ever-higher recording contracts and sold A&M to Polygram for an estimated $500 million. They remained at the label, but clashed with Polygram's management and left in 1993, one of their last signings a singer-musician from Kennett, Missouri: Sheryl Crow. (Alpert and Moss later sued Polygram for violating their contract’s integrity clause and reached a $200 million settlement.)

For a few years, Alpert and Moss ran Almo Records, where performers included Garbage, Imogen Heap and Gillian Welch.

"We wanted people to be happy," Moss told The New York Times in 2010. "You can't force people to do a certain kind of music. They make their best music when they are doing what they want to do, not what we want them to do."

Associated Press writer Beth Harris contributed from Los Angeles.